- NEWS

- ABOUT

- THE FILMS

- Bring Me The Head Of Henri Chrétien! by Billy Roisz & Dieter KOVAČIĆ

- #43 by Joost Rekveld

- Chrome by Esther Urlus

- Colterrain by Tina Frank

- Deorbit by Makino Takashi & Telcosystems

- Louver by Björn Kämmerer

- Lunar Storm by Rosa Menkman

- Pyramid Flare by Johann Lurf

- V~ by Manuel Knapp

- Walzkörper-

sperre by Gert-Jan Prins & Martijn van Boven - rift by hc gilje

- Persistence of the Vacuum Without Grounding Definitions by Lukas Marxt

- Atmospheric Feedback Loops by Susan Schuppli

- Yujiapu by Karl Lemieux & BJ Nilsen

- BOOK

- FLICKR

- VIMEO

- EVENTS

- INTERVIEWS

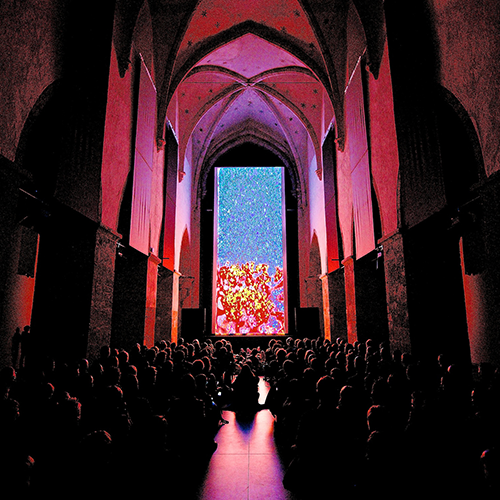

Louver

Previous: Lunar Storm Next: DeorbitLOUVER BY BJŐRN KÄMMERER

10'30''

COLOUR

‘What are we watching?’ is the first thing viewers of Louver might ask themselves. Connoisseurs of Kämmerer’s work are aware that we are possibly witnessing a perceptual illusion caused by the mysterious hypnotic ‘two-dimensional’ movements of a light-object. Our distracted senses are unable to determine if we are observing the ‘real thing’ or abstract patterns of ‘digital light’. Here, we might also try and seek structure, some mathematical point where the movements are conducted, so they can reveal the meaning of the image. But it soon becomes apparent that the subject is Time itself: the time that is needed for the mysterious patterns to develop their own rhythms, and then to disappear into the dark frame from which they emerge. What was once a glittering screen of light grids now appears to us as a one- dimensional dark universe of the unknown.

Louver is a grid, a raster, it can also be a shutter, a way to control the amount of light. There is something hauntingly cinematic in the set-up of this film. First, the format is created by the structure, challenging the vertical with four images on top of each other, moving horizontally, and then acknowledging that the filmed object is a form of light, as is the film itself. And that is what we are actually observing: a movement of light that collapses into an endless stream of associations in the viewers’ mind. If that isn’t film, then nothing is. (Mirna Belina)

INTERVIEW WITH BJOERN KAMMERER:

GOING AGAINST THE VERTICAL

MB What are we actually looking at in Louver?

BK I wanted to use fluorescent light fittings like the ones you see in office or work spaces. That was the basic idea. In the beginning I just wanted them to move mechanically. I also wanted to create an abstract image to avoid any associations an object could evoke. We filmed the set-up for a day in a church. It had to be very fast, very abstract, but then I saw it and thought it was really too fast. It was the same when we used the fittings in a vertical way. That could have been an option but it was an obvious one. But because they swing the lamps never really pass through the image in a straight line, they always curve upwards slightly. And doing it vertically just a bit too obvious. We could have zoomed in closer but after the other films I’ve made, which involved camera tracking, complex movements, dolly shots and so forth, I really enjoyed working with a static camera.

MB So there’s a fixed camera with four lights swinging above it…

BK Yes, and one of the fittings was shorter than the others. It was 1.20 metres long and is the first to move out of the frame; the others are 1.50 metres long. The cords were up to 6 metres long, and with the camera the total height came to 8 metres.

MB Can you tell me about the rhythm in the film?

BK I don’t know if many people notice it, but the film runs backwards. I really wanted – and it sounds romantic – to slowly bring the night into the image without finishing the film. The idea was that the image, which is filled with the image of the light fittings in the beginning, kind of falls apart. It doesn’t really fall apart; the black is something you should anticipate. Two lamps, the one at the top and the middle one, started moving after the short one. We also had one or two seconds between them so nothing in the movement runs in parallel. First you have this graphically perfect idea, but then it doesn’t work out. I like it that the movement is not perfectly straight and you can see all kinds of things.

MB In your films you are interested in the illusion of using movement and light to make something abstract from something figurative.

BK Working in a studio makes it very easy – it’s simple to make objects abstract. I made Gyre, a kind of short story, and Turret, a film with windows, in the studio. I wanted to work outside the studio so I made the film Torque with the passing train tracks. I wanted a very real illusion.

MB How did you approach the vertical format when you started thinking about this film?

BK My first idea was to use the vertical to make something fast, push it a bit. But I decided to be more ‘boring’ and try to move against the vertical. It’s more interesting to watch things moving in a vertical way and discover things in the image, so I thought of filling the image vertically and then breaking it with movements against the format.

MB So you’re setting format against format…

BK Yes. We tested it on the first day when we set it up. I wanted to test it, because it’s a fast movement and you never really know how the image will turn out. Then, of course, we did that vertical movement. Two days later I saw it in a lab and decided it had to be slower. Something moving slowly on a vertical axis in a vertical projection is very dull, which that’s why we stuck to the horizontal. Our approach resulted in more things happening in the image.

MB You usually work with film?

BK Sometimes you hear that its old fashioned, vintage, but right now I really like it as a material. You make an image in a different way from video…

MB …and you have to wait to see what you’ve done because of the processing time.

BK That’s right! You have to wait for this alchemical process to occur. You’re also always challenged by the material. For this film we had two or three reels and one broke. I wouldn’t mind shooting on video, I’m not a film freak, but I still enjoy it. I’ve noticed that film stock is harder to acquire, too.

MB Tell me about the sound in Louver?

BK I usually shoot with an open gate. You never know what will happen, and you capture a bit more of the image. I wasn’t sure if the film should have sound, but it worked out quite well because the sound has a different structure. You can see the rhythm in the raster itself. It works in the same way as the soundtrack, especially when it starts moving.