- NEWS

- ABOUT

- THE FILMS

- Bring Me The Head Of Henri Chrétien! by Billy Roisz & Dieter KOVAČIĆ

- #43 by Joost Rekveld

- Chrome by Esther Urlus

- Colterrain by Tina Frank

- Deorbit by Makino Takashi & Telcosystems

- Louver by Björn Kämmerer

- Lunar Storm by Rosa Menkman

- Pyramid Flare by Johann Lurf

- V~ by Manuel Knapp

- Walzkörper-

sperre by Gert-Jan Prins & Martijn van Boven - rift by hc gilje

- Persistence of the Vacuum Without Grounding Definitions by Lukas Marxt

- Atmospheric Feedback Loops by Susan Schuppli

- Yujiapu by Karl Lemieux & BJ Nilsen

- BOOK

- FLICKR

- VIMEO

- EVENTS

- INTERVIEWS

Colterrain

Previous: Deorbit Next: ChromeCOLTERRAIN BY TINA FRANK

10'20''

COLOUR

SOUND: COH

AUDIO TO VIDEO: GREGOR GÖTTFERT

my tv has no picture, just vertical colour lines… sound is fine…

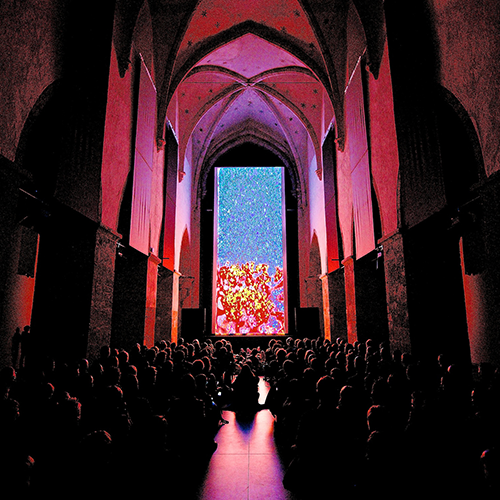

Colterrain, the title of this film, refers to a colourful landscape, a terrain described by lines similar to geographic mapping – in this case a mapping of sound. What you hear is what you see, literally. The audio was transmitted through a Synchronator device that translates audio frequencies into RGB video frequencies.

With this method, the image is actually the music turned into colour and filmed live using analogue equipment. Listening to the sound evolving, one becomes a witness to colourful movements. At some point we no longer know which comes first: is it the lines going inwards or outwards, or the colours crawling up or down? And why are human beings so strongly connected to moving lines anyway? A line implies action because it is created by a dot moving from one place to another. The moving line becomes a field, which in turn is an area of colour. Like Rothko’s Colour Field paintings, Colterrain also strives for an intense experience between viewer and image.

Colterrain intentionally plays with the vertical nature of the Vertical Cinema project. The visual split in the centre of the screen becomes a portal to other dimensions, a visual door to the world of sound.

INTERVIEW WITH TINA FRANK:

A COLOURFUL MAPPED LANDSCAPE OF THE MUSIC

MB Can you explain the title of your film, Colterrain?

TF Colterrain tries to map music into colours, translating it from one perspective to another. It’s comparable to trying to merge two different perspectives. Imagine a physical terrain translated into a map. Such a process of translation gives us another perspective that differs from the one we perceive from where we are standing; we also gain an overview and a feeling of what is around us. Mapping also describes the process of how I arrived at the images, which is driven by analogue technology. The music was played through the Synchronator device [built by Gert-Jan Prins and Bas van Koolwijk], which translates sound into visuals. It is a one-to-one mapping of analogue audio frequencies into analogue video frequencies. Because I use lots of colours I called it Colterrain – a colourful mapped landscape of the music.

MB You mention colour field painters as an inspiration, but you’re also a designer who is interested in colours – and lines.

TF As a designer aware of how our visual perception works, I’m tremendously interested in lines. But in Colterrain are we looking here at one line, two lines or many lines? Because of the vertical split-screen-setup, does the movement of the lines in the film come from a single central line or from multiple lines? Is this movement going in or out? We are conditioned to look at a line and understand what it could mean. Vertical lines remind us visually of tall grass, of trees, of things growing vertically. A horizontal line could evoke the horizon, the sea or waves. The meanings and connotations of vertical and horizontal lines are clearly very different. We always have to look at what we see and decide whether it suggests something dangerous or confrontational – like a lion or a car – or whether it’s something pleasant. Horizontal lines, especially if they remind us of the horizon, aren’t dangerous: they won’t race towards us at high speed…

MB Did the vertical format influence your approach to your film?

TF I discussed the vertical format with Martijn [van Boven] and he said that for him it meant a complete rethinking of the format. Whereas for me… I’m a designer, I’m used to designing for different formats, so it wasn’t an issue. What I underestimated in the beginning was its extreme height and narrowness. Cinemascope turned 90 degrees is a very slim format. That took me a while to get used to.

MB You’ve performed live with the Synchronator…

TF Yes, as a member of the Synchronator Orchestra at the Sonic Acts Festival in early 2013. But I’m rather a newbie to the Synchronator – I got it a year ago at Kontraste. It’s great, I love it! I also bought this incredible physics lab device, a function waveform generator that creates frequencies on its own and now I’m feeding these frequencies into the Synchronator… The next step is to get lots of different devices, combine them and really play with the frequencies. The Synchronator has made me think in an analogue way of processing frequencies to create images. Fascinating stuff! And it’s completely changed my approach – which is obvious because until then I was only working digitally: layouting, generating, programming, whatever…

MB Have you worked with film before this project?

TF I have no experience with celluloid. I’m a digital person. Everything I create is in bits and bytes. Some of my designs are printed on paper, but the layouts and especially my movies are stored on hard disks and shown on the Internet or iPads or whatever. Seeing the first test strip of my film was really weird. All the classic filmmakers, like Brakhage, Lye, and many others painted on film or scratched it, creating lines that run along with the film. In that sense my movie is peculiar, because my lines, although vertical when screened, are rotated 90 degrees to the running film. So when you look at the filmstrip you never see the movement. These movements come to life from frame to frame, but only because it was calculated, because it was rendered onto the celluloid.

MB And the colours on film…

TF Matteo [Lepore] did such a great job with the transfer. He said my material behaved strangely, jumping up and down, and he had to keep it sitting on the couch like a four year old. [Laughs] Orange could become brown or yellow during the transfer to celluloid. The film has a different look from what I saw on my computer screen. It’s much darker, more mystical, deeper. That comes with the material.

MB So it went from analogue to digital…

TF From analogue to digital and then rendered back again onto analogue material. And what is especially interesting – also when it comes to archiving – is that my film has become an object. My film in a silver box! I would love to have a copy, own it in a physical way.

MB Is it like producing a design that materialises in a book or an object?

TF Yes! This last year I’ve been carrying around a piece of filmstrip from Peter Kubelka’s Antiphon [2012]. I was at his lecture in the Gartenbaukino during the Viennale [Vienna International Film Festival] where he screened it. He unravelled a copy of the film through the audience, from one side of the cinema to the other, from the back to the front. Everyone held the film, then he gave us scissors and we cut it into pieces… Ever since then I’ve been carrying this piece of film with me.

MB Can you tell me about the soundtrack and your collaboration with Ivan Pavlov (aka COH)?

TF We’ve been working together for many years and were in constant contact for record cover designs or other projects. At the beginning of this year I was in the process of creating a cover for him when I rehearsed with the Synchronator Orchestra in Amsterdam. I had his new tracks with me and played them through the Synchronator just to see what the frequencies look like. His sounds produced really interesting images, so when Sonic Acts approached me with the idea of Vertical Cinema I asked Ivan if we could use his sounds as the basis for the film.

MB Was it difficult to make a film as a commission?

TF Actually no, it was a piece of cake! But I was lucky: every so often a project comes along that just runs smoothly. Everything happens exactly as it should. This was one of those. There was no stress from the moment we began until it ended – and I actually finished before the deadline! This rarely happens. The same thing happened with Chronomops [2005]. I think both of these films are really good works. I wouldn’t change anything about them.

Excerpt from COLTERRAIN on Vimeo .

Still from 'Colterrain'

Still from 'Colterrain'

Still from 'Colterrain'

Still from 'Colterrain'

Making of 'Colterrain': the artist's working space

Making of 'Colterrain': test screening